Campaigning for mobile home park rent protection from her living room in Huntington Beach was not on Carol Rohr’s retirement to-do list. Kayaking trips and excursions are more at the speed of this 65-year-old man.

But Rohr now spends up to 12 hours a day working to secure rent stabilization for mobile home parks during the city’s November ballot — reading city handbooks, canvassing the neighborhood and meeting council members. municipal. She became president of the association of owners of the Skandia Mobile Country Club where she lives.

“I had no idea when I went for it, that it was going to be what it was going to be,” Rohr says.

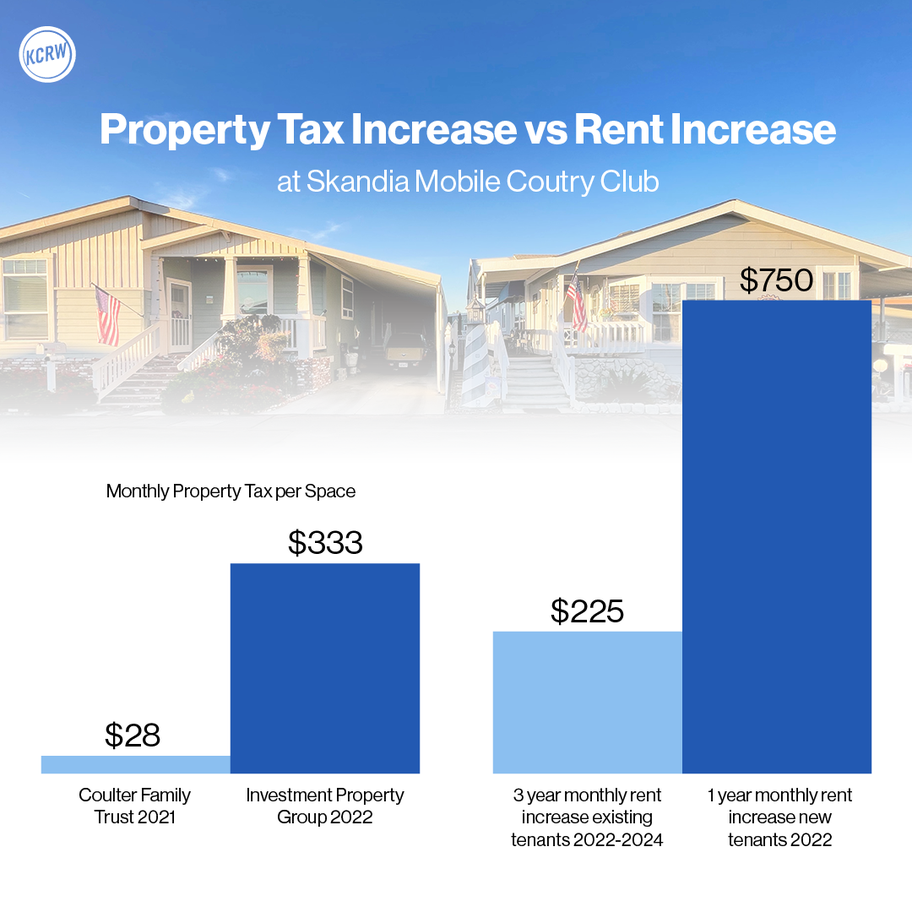

It all started in August 2021 when corporate real estate owner Investment Property Group bought the family-owned Skandia mobile home park. Soon, IPG announced that rents would increase by $225 over the next three years to cover a more than tenfold increase in property taxes when the land was transferred to them.

This rent only pays for the use of the land under the mobile home. It does not include the cost of buying the house and maintaining it. This is the responsibility of landlords like Rohr, who believe that the new fees amount to excessive rents.

“It was obviously predatory behavior, thinking they could just buy it, raise the rents and cover the new taxes. That’s wrong. It’s evil,” Rohr says.

Carol Rohr, president of the Skandia Mobile Country Club Homeowners Association, listens during a meeting with residents about rent hikes at their mobile home park. Photo by Megan Jamerson.

What happens at Skandia Mobile Country Club is by no means unique. Big investors like IPG are buying up parks across the country. Billions of dollars were invested in this type of affordable housing last year, with record 22% of that money from businesses, according to Bloomberg News.

IPG bought Skandia for $58 million and owns 100 other parks across the country.

Julie Rodriguez, president of IPG property management, defended the new rents at a Huntington Beach City Council meeting in February. She said the increases for existing tenants don’t come close to covering the increase in property taxes. “But we’ve kept the increase low to ensure every resident can stay at home,” she said.

IPG plans to increase rents by $75 over the next three years, which means monthly charges for Rohr will total $1,590, an increase of 18%. Meanwhile, rents for new tenants are rising 50% this year to $2,195 per month.

That might not seem like much for a place less than two miles from the beach, but Skandia is a park for people aged 55 and over, Rohr says. “There are a lot of people on fixed incomes who won’t be able to afford higher rents. [and] who have no place to go.

The figure above shows the increase in property taxes compared to rent increases at Skandia Mobile Country Club after Investment Property Group purchased the park from the Coulter Family Trust in August 2021. Figure by Mike Royer/KCRW.

Big investors make that profit by raising rents, says California Housing Partnership consultant and tenant advocate Jerry Rioux. Rioux says California’s tight housing market allows large investors to make “a pretty safe and substantial profit buying mobile home parks in California.”

He adds: “That’s all they care about. If they can make more money, they will do it legally. And they will push the envelope.

IPG did not respond to KCRW’s requests for comment, but representatives told council members they were participating in a rental assistance program that provides up to two years of rent relief to a number limited number of residents. And they said they were investing in the property with things like $85,000 to resurface the streets and $15,000 for new pool furniture.

This all sounds familiar to Patricia Taylor. IPG bought its mobile home park near Huntington Beach three years ago. This year, Taylor’s rent has gone up from $85 to over $1,500 a month. Taylor, who is over 80 and lives on Social Security, says she no longer has the budget for simple pleasures like going to a restaurant.

“I’m very careful about what I spend and I don’t do a lot of entertainment. I do not intend to travel. I can’t go everywhere,” Taylor says. “My income pretty much covers the necessities and that’s it.”

In 2014, she worked on a grassroots campaign that failed to secure rent stabilization on the Huntington Beach ballot. Now she’s working with Carol Rohr and a dozen other seniors to kick-start the effort during weekly meetings at Rohr’s home. Stabilizing rents specifically for mobile home parks would protect tenants like her from steep rent increases, while allowing landlords like IPG to raise rent at a regulated rate.

A dozen seniors gather in Carol Rohr’s living room at the Skandia Mobile Country Club to discuss a strategy to secure rent stabilization in the city of Huntington Beach’s November ballot. Photo by Megan Jamerson.

“We’re trying to get the city to help us protect their senior citizens,” Taylor says. “Supposedly Huntington Beach is the city of compassion and we hope it will eventually be the case.”

Nine California counties, including Los Angeles, and 86 California cities now have some form of rent protection for mobile home tenants. The pressure is high in places like Huntington Beach, where six of the 17 mobile home parks are now owned by businesses.

There is now more sympathy for the city council on rent stabilization than during the last push in 2014, and neighboring Santa Ana passed a version of rent stabilization last year. Taylor says Orange County mobile home residents are also becoming more outspoken about the issue. “It’s just not ethical. It is not fair. This is not reasonnable. So that pushes you to take action to try to get something to help those people.

Tenants like Taylor own their mobile homes, and if rents get too high, she could have it moved. But it costs tens of thousands of dollars. Selling is also not a good option, as homes generally lose value as rents go up.

For those who cannot afford the higher rent, there is the threat of eviction. Taylor says she might be able to handle rent increases for another two years. After that, she will try to sell her house and go live with her 90-year-old brother and his wife in Colorado Springs.

Taylor worries about the possibility of losing her two-bedroom house and the flower garden she has cultivated for the past 12 years. “I love my home and I don’t want to go anywhere else, and I don’t want to be forced into it because of the situation,” she says. “I love where I live. I have a cat for a companion and he seems to be very happy there too.

Taylor, Rohr and the dozen other seniors who meet for weekly meetings have until August to get rent stabilization on the ballot. The first option is to collect 29,000 signatures. The second option is to convince the city council to sponsor the ballot initiative itself.

Neither will be easy, and the hard work doesn’t stop there, Rohr says. Once the measure is passed, she will lead a campaign to convince a majority of the city’s inhabitants to support it.

“The hardest thing is the pressure of failure. At least 3,000 to 5,000, maybe 6,000 mobile home residents in Huntington Beach, whether they know it or not, are counting on us,” says Rohr.