How mobile apps could boost bank revenue

Strong customer demand for mobile banking apps could provide an opportunity to increase revenue for some institutions.

Retail banking customers highly value their mobile apps, and some may even be willing to pay a monthly fee to use them. S&P Global Market Intelligence’s Mobile Money survey of 3,897 U.S. banking app users, conducted from Jan. 23 to Feb. 3, found that 21% of respondents were willing to pay $3 per month for their current mobile banking app. and 40% willing to pay $1 per month.

Extrapolating company-specific survey results to mobile user estimates, S&P Global Market Intelligence concludes that JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp. and Wells Fargo & Co., which together held 35% of US deposits at the end of 2015, could add hundreds of millions of dollars in revenue by charging small monthly fees for mobile banking. Or they might find that many retail depositors using their apps would be less responsive to rate changes than some others, allowing institutions to slowly increase deposit costs if rates rise.

Estimation of potential revenue from banking applications

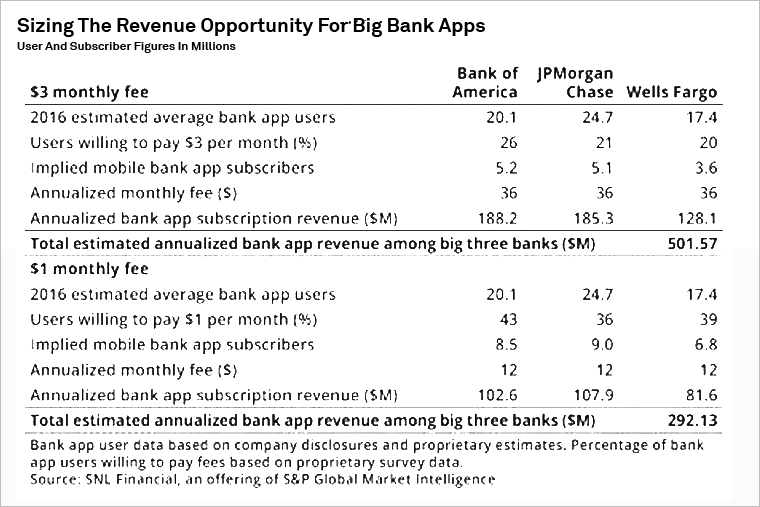

S&P Global Market Intelligence has estimated how much revenue the three largest banks could hypothetically generate by charging for banking apps customers are already using. Since competitive market pricing is not available for mobile banking apps, we used pricing data derived from the Mobile Money survey. This provides the percentage of banking app customers willing to pay $1 or $3 per month to use their bank’s mobile app.

The analysis used data from survey respondents who identified themselves as customers of JPMorgan, Bank of America and Wells Fargo. Not only do these banks hold a large portion of US deposits, but they report mobile banking app users in quarterly reports.

S&P Global Market Intelligence estimated the number of banking app users for each of the three banks through 2016, then used those 2016 year-end estimates and published year-end banking app user numbers. year 2015 to obtain the average banking app users in 2016. Then we multiplied the estimates for the average banking app users in 2016 by the respective percentage of voluntary app purchasers of each bank from the results of the survey to obtain the implicit subscribers to the mobile banking applications.

To calculate the annualized revenue, we multiplied the implied mobile banking app subscribers by the hypothetical fee of $1 or $3 per month. In this analysis, a price of $1 per month generates total annualized revenues of $292.1 million for JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America and Wells Fargo. When the price is raised to $3 per month, the potential annualized revenue jumps to $501.6 million.

Survey results sometimes tend to overestimate willingness to buy, compared to real-world observations, so the analysis also generated a lower estimate based on a much more modest adoption rate. Even if the number of voluntary app buyers were 10 times lower than the survey suggests, that would represent an annualized revenue of $50.2 million at a price of $3 per month and $27.2 million. dollars at a price of 1 dollar per month among the three banks.

Demand for mobile banking apps is relatively inelastic between $1 and $3 per month, meaning a bank could theoretically maximize its revenue by charging more for its app, despite losing millions of app users. . The loss of deposits is a serious inconvenience if customers who do not want to pay for a mobile banking app decide to do business elsewhere. But as long as banks invest in their mobile apps to collect deposits, they can also consider other ways to use them to generate revenue.

To load or not to load

The decision to charge for a service that is currently free is not easy. Unless many banks start charging fees, customers who don’t want to pay for mobile banking could easily switch to a competitor. When interest rates rise, competition for retail deposits is likely to intensify, as customers have more incentive to transfer their money to accounts paying higher rates on deposits. Banks will likely have to offer their customers some return if rates rise, but they might be able to raise deposit rates by lower amounts than their peers if they offer a more attractive app. Alternatively, banks could potentially offset some of the costs with additional fee revenue if they start charging for their apps, at least for some customers. With net interest margins under pressure and the cost of regulatory compliance weighing on banks, there are many other reasons to look for ways to increase fee income.

Our research did not reveal any bank that charges a fixed monthly fee for mobile banking apps. Charging for a previously free service can attract public attention and backlash from customers, as Bank of America learned in 2012 when it considered introducing fees of $6 to $9 a month for many customers. Even so, customers now find that there are more conditions attached to free checking accounts than in the past, such as the need to maintain account balances above a certain level or to use multiple products at the same time. bank. If banks wanted to impose fees on basic mobile apps, they could use a similar playbook to decide which customers would be charged fees.

Banks could generate revenue from mobile banking by offering premium apps or by starting to charge for apps customers already use. Some banks charge for certain services in their apps. For example, US Bancorp charges customers using the mobile remote capture tool to deposit checks, and SunTrust Banks Inc. collects fees on person-to-person money transfers in its banking app.

A premium mobile app could incur monthly subscription fees and offer a superior suite of features that customers want but currently don’t have, such as budgeting tools. About half of Mobile Money survey respondents were happy with their mobile banking apps, but many more identified features they would like to see.

Various white-label technology companies are already helping banks extend the capabilities, functionality, and value of their apps. Moven, which started out as a competitor to depository institutions, has shifted to leveraging its mobile and technology expertise to partner with banks looking for a more dynamic and competitive mobile app. Its first such collaboration was with the Toronto-Dominion Bank in 2016. Moven designed a new personal money management platform called TD MySpend, a spinoff of the mobile budgeting app Moven offers to its own account holders. online checks. TD Bank does not charge customers for this service.

Ultimately, the question is whether mobile banking has become part of the industry’s customer service base or whether depositors might be willing to pay in fees or lower returns.